Did Tolkien Hide an Easter Egg Between Old Man Willow (a Tree) and the Barrow-downs (a Tomb)?

How the enigmatic Tom Bombadil leads to a fun insight about Tolkien’s faith and storytelling instincts

Some weeks ago I finished a fascinating book about Tom Bombadil, the most elusive figure in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. “In a mythical Age there must be some enigmas . . . Tom Bombadil is one (intentionally),”1 Tolkien once said of him, which is his way of saying that Tom was meant to be received like an unsolvable riddle.

Fair enough, although if you’re anything like me, that sort of mystery only makes you want to consider him all the more. So you can imagine my reaction when I reached the last page of this book about the mysterious man in a bright blue coat and yellow boots, glanced down at the bottom, and found a solitary footnote waiting there like the one ring gleaming at the bottom of the Gladden River:

“Here’s a postscript to the postscript, a final thought that occured to me as I was putting the last touches on this book: the first time that Tom saved the hobbits was at a tree, and the second time that he saved them it was at a tomb. For those pondering what Tom represents, that’s an even more encouraging thought.”2

An encouraging thought indeed.

Recently I shared a picture of this footnote and a reader named Malcolm replied: “Without checking, I bet it was three days between Old Man Willow and the Barrow-downs.” There was something delightfully confident about that guess, so I decided to check. I reached for Tolkien’s Appendix B, The Tale of Years, and traced the dates. And, would you know it, Malcolm was right. Old Man Willow captures Frodo and his friends on September 26, 3018 and the Barrow-wight traps them on September 28, 3018.

That’s three days from tree to tomb.3

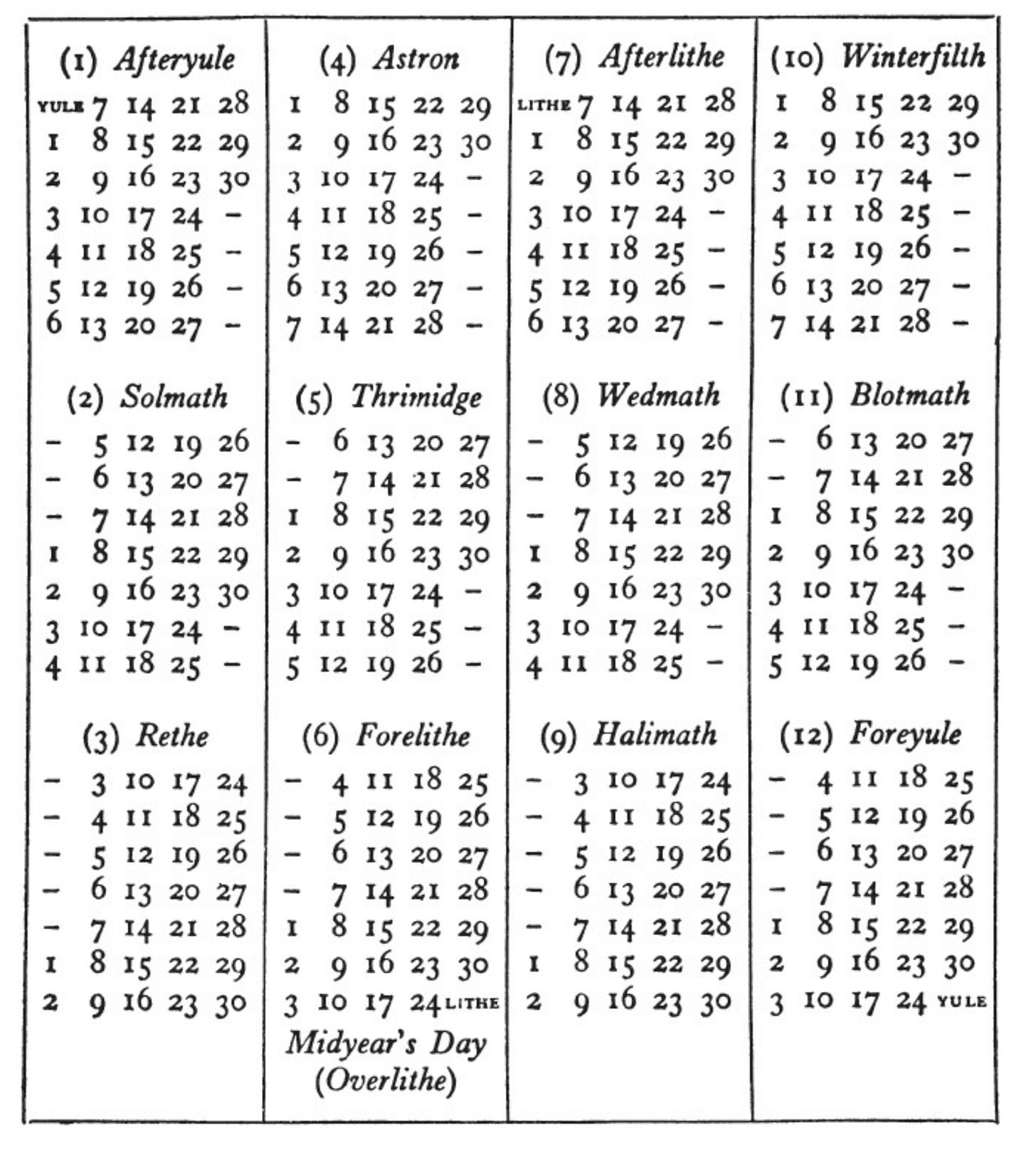

Now, after that, another ambitious reader named Joseph jumped in: “Could we figure out what days of the week those were?” Which is the exact sort of question that ruins an afternoon in the best possible way. So I opened Appendix D, and started sorting through the Shire Calendar For Use in All Years.

What I found made me sit back in my chair.

There is a high likelihood Tolkien positioned those two rescues on the equivalent of our Friday and Sunday.

Tolkien built the Shire calendar so that its dates always fall on the same weekday every year, since “Mid-year’s Day had no weekday name,” which keeps the weekly cycle from shifting. So, when you trace the dates in Appendix B and line them up with the fixed weekday pattern in Appendix D, a striking picture emerges. Old Man Willow likely happened on the Shire equivalent of a Friday and the Barrow-down rescue on the Shire equivalent of a Sunday.4

What this means is that, whether by deliberate symbolism or by the invisible milieu of a mind shaped by Christian imagination, Tolkien may have worked a striking “holy week” pattern into the early chapters of The Fellowship of the Ring: a fall into darkness on Friday when Tom rescues the hobbits at a tree, a silent rest on Saturday as they dwell in Tom’s house for the day, and a deliverance bursting into the light on Sunday when Tom rescues them at a tomb.

In other words, Tolkien hid an ‘Easter egg’ in plain sight, and fittingly enough, it’s actually about Easter.

“the Son of Man must be … crucified [tree] and on the third day rise [tomb]” (Luke 24:7)

Now, to be sure, I am reminded how in the Foreword to The Lord of the Rings Tolkien famously said, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence.”5

However, at the same time, Tolkien wrote to his friend Robert Murray that, “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision.”6 In the letter he goes on to explain that this “religious element” is absorbed into the story, even if it’s not expressed by overt allegory.7

To press the point, Tolkien writes in his Foreword,

I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse ‘applicability’ with ‘allegory’; but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author. An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience.8

What this means is that Tolkien’s faith may never have turned his stories into sermons, but it did inform how they were written. Indeed, he disliked didactic fiction, and he pushed back whenever readers tried to cast Middle-earth as a tidy allegory, so we want to tread carefully here, but, even so, while The Lord of the Rings isn’t a sermon, it is a world where grace, sacrifice, and providence run with the grain of Lothlórien wood. The faith is there, even if the tale never bends under its weight.

That’s why this small detail about a three-day span with deliverance at a tree and again at a tomb feels so aligned with Tolkien’s craft. He never wrote propaganda, and I appreciate that. He wrote fairy-stories in the older and richer sense, tales that carry what is true about the world into the imagination through beauty and harmony rather than through debate and argument. For him, a good story doesn’t preach so much as it participates with the Great Story. And here, within the first hundred pages of his epic, we glimpse a pattern that has steadied Christian hope for two millennia, appearing like a watermark on the page.

I’ll admit, I found it moving. There’s something brilliant about it, the way a man’s convictions seep into his craft without ever turning the craft into a tract. It reminded me that truth doesn’t always need to be argued and debated, because what’s true is true.

And, while it makes me grateful for Tolkien’s imagination, it also makes me want to pay closer attention to my own, because grace has a way of leaving fingerprints on everything it touches.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), Letter 144.

C. R. Wiley, In the House of Tom Bombadil (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2021), 106.

See J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: Illustrated Edition (New York: William Morrow, 2021), 1082–1098.

Tolkien structures the Shire calendar so that its weekly rhythm never shifts, and this is the key, I think, that allows the weekday reconstruction. In Appendix D, he states that “Mid-year’s Day . . . had no weekday name” and that “the same date in every year had the same weekday name.” I take these two rules to mean that the extra festival days are “outside” the week, so the cycle never advances or retreats from one year to the next. Because of this, once any date in S.R. 1418 has a known weekday, while every other date in that year inherits its weekday automatically. Tolkien anchors this in his chronology when he places 1 Yule of S.R. 1418 on a Friday (see Appendix D, “The Calendar,” table note 1). Working backward from 1 Yule (Friday) through Foreyule and the preceding months yields fixed weekdays for all Shire dates; under this system, Halimath 22 seems to emerge as a Monday, placing Halimath 26 (Old Man Willow) on Friday and Winterfilth 28 (the Barrow-downs) on Sunday. In other words, Tolkien’s calendar logic creates a stable pattern in which the Old Forest rescue aligns with a Friday and the Barrow-wight deliverance aligns with a Sunday, forming a subtle three-day arc of deliverance. See J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: Illustrated Edition (New York: William Morrow, 2021), 1106–1112.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: Illustrated Edition (New York: William Morrow, 2021), xix.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), Letter 142, 172–3. Italics mine.

Robert Dobie extends this thought in his chapter “Of Niggle, Mythopoeia, and the Secret Fire,” where he writes, “for a writer who claimed on several occasions to dislike allegory, “Leaf by Niggle” is for all intents and purposes an allegory.” Robert Dobie, The Fantasy of J. R. R. Tolkien (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2024), 1.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: Illustrated Edition (New York: William Morrow, 2021), xix.

If I know anything about Tolkien, nothing is an accident.

Thank you from the bottom of my heart for this. Wow.